Informe mundial de las Naciones Unidas sobre el desarrollo de los recursos hídricos 2020: agua y cambio climático

Indigenous technologies “could change the way we design cities” says environmentalist Julia Watson

Indigenous communities are pioneers of technologies that offer solutions to climate change, according to designer and environmentalist Julia Watson.

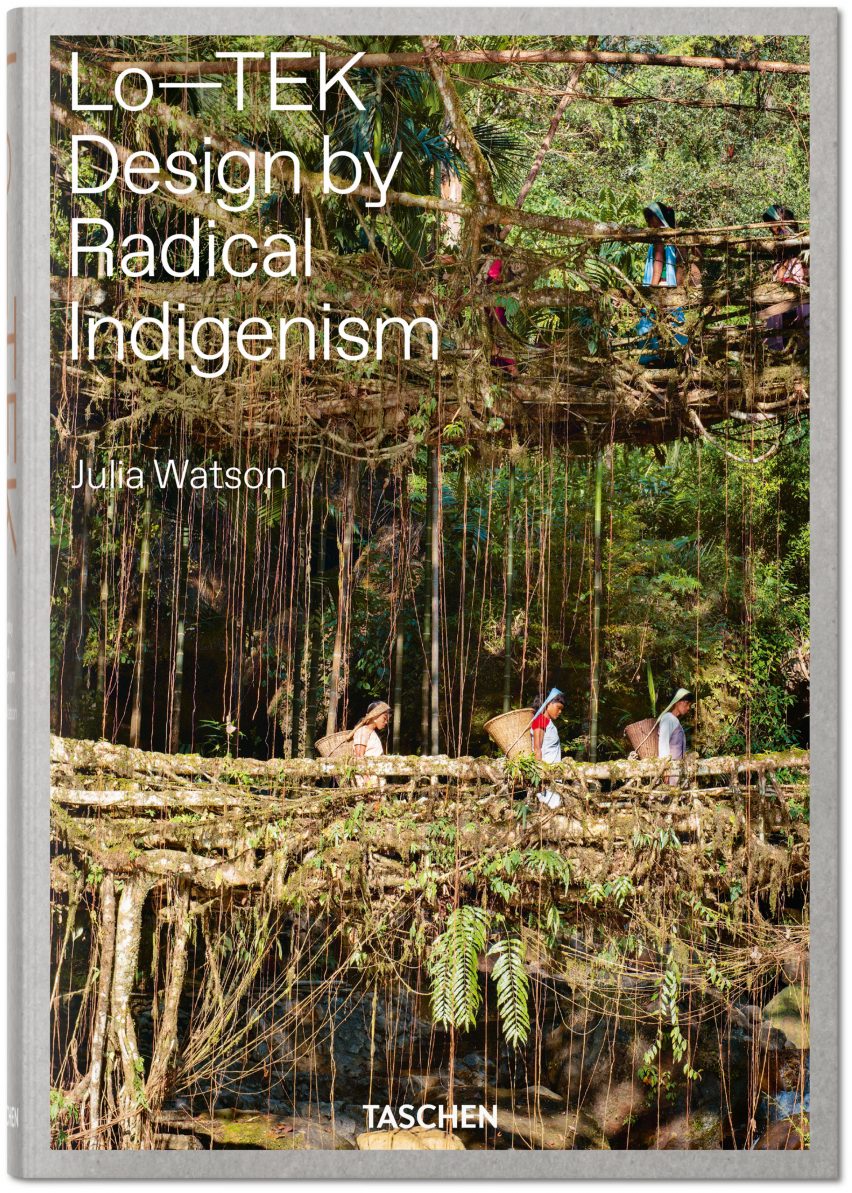

In her new book, LO–TEK Design by Radical Indigenism, Watson argues that tribal communities, seen by many as primitive, are highly advanced when it comes to creating systems in symbiosis with the natural world.

“There are so many examples,” she told Dezeen. “They have increased biodiversity, they’re producing food, they’re flood mitigating, they’re resilient in terms of foreshore conditions, they’re cleaning water, they’re carbon sequestering.”

“They have all of the natural qualities that we’re really interested in, in terms of ecosystem services, but they’re completely constructed by man,” she added.

Progress requires a new toolkit

Watson believes that the tech industry is more limited in scope than people realise, based solely on a concept of high-tech that developed after the industrial revolution.

She calls for this industry to adopt some of the principles of indigenous design, many of which are thousands of years old, to help cities around the world to not only mitigate the impact of climate change, but to be resilient for the future.

“I have a really clear vision for what the middle ground could be, how we could start to explore these technologies and think about how they could change the way we design cities,” she said.

“We can’t really move forward using the same toolkit that got us to the place we are now,” she continued. “We can’t just keep reusing the high-tech and that type of thinking to solve the problems that created the problems.”

LO–TEK design philosophy

Watson, who teaches urban design at Harvard GSD and Columbia GSAPP, has spent six years developing her concept for LO–TEK. Not to be confused with low-tech, it incorporates the acronym TEK, which stands for traditional ecological knowledge.

The book highlights a series of case studies, in mountain landscapes, forests, deserts and wetlands.

Examples include the Jingkieng Dieng Jri Living Root Bridges, a system of living ladders and walkways created by the Khasi tribe of North India, and the Totora Reed Floating Islands, a series of manmade islands created from reeds in Peru.

Some are directly comparable with western-developed alternatives, as is the case with the Bheri Wastewater Aquaculture in Kolkata, a natural wastewater treatment system that cleans half of the sewage for a city of 12 million people.

Symbiotic relationships with nature

“LO–TEK reframes our view of what technology is, what it means to build it in our environment, and how we can do it differently, to synthesise the millennia of knowledge that still exists,” said Watson.

“This is about symbiotic relationships, which are the fundamental building blocks of nature. These LO–TEK technologies are born of symbiotic relationships with our environment, humans living in symbiosis with natural systems.”

Watson believes that, with global awareness of the climate crisis growing, and a groundswell of young people up in arms, the time has come to reassess our approach to sustainability and innovation.

“I can see change happening because I see it every day,” she added. “This is a huge step in the right direction towards shifting, elevating and reframing how we build and how we urbanise.”

Read on for the interview in full:

Amy Frearson: Can you start by explaining what LO–TEK is?

Julia Watson: LO–TEK is a term that I developed. Obviously low-tech is a term that we use in architecture and innovation, which means rudimentary or primitive technologies. It’s seen as utilitarian, a lower type of technology, and often has a relationship to social innovation. I think that there’s a confusion that perhaps nature-based technologies might be of that same category, or that they’re not a technology at all because they’re so synthesised with our natural environments.

It’s working in contrast to the concept of high-tech, which is the fascination and evolution of industrialism. We’re in an era where our world is pretty high-tech and so is our industry. We got here because, at a certain time, we said this is what technology is. Of all the thousands of technologies across the globe, including indigenous local technologies, we took a small sliver that was in the view of the people who began our globalised, modernised path forward. That got us to where we are now, which is a fantastic development as a global civilisation, but we’re also in this paradox of being in a world that is threatened by climate change and environmental crises, and that has social and economic off-spins.

So we’re at a point in time where we have this frame of a global view of the world. We still have these nature-based technologies out there, although most are threatened and we’ve lost a lot of them. And it’s a time where we’re looking for something different in the urban environment, and in the way that we build and relate to nature. It is a moment for us to take stock, to recontextualise that framework of industrialised, digital high-tech or high-tech living, which removes us from nature, and reframe the potential of the toolkit in our urban environments. What’s the toolkit that we have to relate to nature? And how do we do it differently moving forward?

We package these things as very new, contemporary, modern and urban technologies but they have these long lineages of millennia-old knowledge

And so the LO–TEK also incorporates TEK, which means traditional ecological knowledge. It’s a term that’s used in human ecology, which is where a lot of this work grounds itself, in the realm of the sciences. It’s saying, if these are technologies that are simply constructed, made from local materials, they are not within the frame of high-tech. But it’s not low-tech because these are really complex ecological relationships, it’s nature-based technology. It’s not primitive, it’s incredibly innovative in trying to find solutions for the urban or peri-urban networks that feed our cities, trying to find solutions for climate change and resilience. We’re looking to these types of solutions but we just don’t have a huge toolkit at this point in time.

LO–TEK reframes our view of what technology is, what it means to build it in our environment, and how we can do it differently, to synthesise the millennia of knowledge that still exists. Technology has been born of that and is symbiotic with ecological processes, from the micro to the macro.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me a bit about your background and what led you into this field?

Julia Watson: I began as an architect, 22 years ago in Australia, studying in Queensland at UQ, where I took a course called Aboriginal Environments. Obviously the colonial and Aboriginal world in Australia is a really charged topic.

My family is English and Greek, and my mother was a first-generation immigrant from Egypt, so as a kid growing up I had a very colonial worldview frame without even knowing about it. When I started learning about the Aboriginal environment, it was such a different way of looking at the world and I was fascinated. About a year later, I graduated and was going to live in London but I stopped in Borneo on the way. I had been reading about what was happening in Borneo, with the loss of orangutangs and primal plantations, and I was looking for this tribe called the Penan people. I’d been reading about a Swiss environmentalist who had been championing this group of forest dwellers to stand up against the Malaysian government because they were taking away their forest to develop into palm-oil plantations. He had gone missing, but he had documented this tribe that no one had really seen before. I was fascinated with going to the jungle and looking for this tribe. I went to Borneo for a month and I found the tribe eventually. They were living in this encampment on the side of a river that was obviously not the way they’d ever lived. It was so sad.

I went to London, then came back, but kept on studying this idea of what it means to be an indigenous person and how you see the landscape that you live in. I wanted to know why is it so different to the way that I was brought up, to the way that so much of the world relates to the natural world, and what is still there in that relationship. What have we lost with the pathway of colonialism? Can we ever find a middle ground?

That led me to Harvard, where I went to study sacred landscapes, looking at why they are sacred and how you conserve them. I discovered that most of these sacred landscapes are about protecting resources that makes human survival possible, like freshwater or farms. They’re basically about protecting the earth, because human survival is dependent upon that. I won an award when I graduated, so I was able to go on pilgrimages to sacred sites around the world to study them. I did trips to Mount Kailash in Tibet for a Saga Dawa Festival and to a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Bali.

Out of that, I started teaching contemporary landscape technology at Columbia, where I started to realise that a lot of these technologies, like green roofs, have been around forever. We’re making artificial wetlands that clean water, but there’s already natural wetlands that do that. We package these things as very new, contemporary, modern and urban technologies but they have these long lineages of millennia-old knowledge. It got me thinking, how many others are out there that we’re not looking at yet? How closed-down is our frame of what we package as technology?

That’s where the book came from. I asked, could there be 50 more technologies like this? Could there by 100? In the book there are 120, and that’s just a flashlight in the dark, of one person doing this with no funding, just driven by curiosity and some wonderful students that took on the cause and wanted to work alongside me.

Amy Frearson: Can you pick out some of the most radical examples of LO–TEK from the book?

Julia Watson: The case study that I think people understand the most succinctly is the East Kolkata wetlands, which is a sewage wastewater treatment system in Kolkata. It was born a few hundred years, so it’s not like it’s a 6,000-year-old technology, but it was born from a group of Bengalese farmers who were living on the outskirts of Kolkata, which is now a city of 12 million. There’s a collective of farmers that treats sewage water coming out of the Hooghly River. A lot of the sewage from Kolkata goes into a system that leads to this wetland, and they put it through a series of processes. They have settling ponds and they have ponds where they introduce fish. It’s a really large system of wetlands that is completely manmade and run by village cooperatives. They’re cleaning wastewater and producing vegetables for the city, while saving millions of dollars a year compared to the operating costs of an actual sewage treatment plant. It’s actually cleaning half of the sewage coming out of a city of 12 million people, every single day. You can see that that application on the periphery of a city like New York or London, if there was municipal will and a real mind-shift towards nature-based technologies.

It’s a reframing of understanding technology, how we relate to our natural environment and what that means

Another technology that I think you can recontextualise is in the Amazon rainforest in Brazil. There is a tribe called the Kayapó that introduces hundreds of different species of plants in an agroforestry system within the rainforest. It doesn’t destroy the rainforest but is incredibly productive for food. So you have the Amazon on fire because of clearcutting for cattle ranching, but in that same rainforest you have a community who live in the rainforest, obviously at the same scale, but doing a different type of farming that integrates into the canopy of the rainforest and still produces food. There are these two completely different types of systems, coming up against one another, but no one’s learning from one another. There’s no adoption of a symbiotic agroforestry productive food system or allowance of the co-benefits of keeping the Amazon rainforest but also producing food, even though you see those types of systems across the globe.

Another very similar system is at the base of the southern slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. The Chagga is one of the richest, most-educated communities in Tanzania, in that part of Africa. They have what they call the kihamba, which is a banana plantation that takes you can two and a half hours to drive through. It’s the size of Los Angeles, this area of land. They’ve got an estimated 500 species in that forest that retains the original forest canopy, but they’ve introduced about 250 new species of productive bananas, coffee and different plant species. They’ve managed to figure out a way to retain the complexity of the natural rainforest but also integrate a really complex agroforestry system that is incredibly productive, which has made them one of the most economically advanced communities in that region.

Amy Frearson: How would you sum up the case studies you’re found so far?

Julia Watson: It’s a reframing of understanding technology, how we relate to our natural environment and what that means. And if we keep on looking, there are so many examples. They have increased biodiversity, they’re producing food, they’re flood mitigating, they’re resilient in terms of foreshore conditions, they’re cleaning water, they’re carbon sequestering. They have all of the natural qualities that we’re really interested in, in terms of ecosystem services, but they’re completely constructed by man. They use complex ecological relationships to drive them, but they are low on embodied energy. They produce a certain type of community and cultural activity, and they allow for that community to live really closely and harmoniously with their environments.

Amy Frearson: Earlier you said you were looking for a middle ground between indigenous technologies and the world of high-tech. Having done this study, do you think it is possible to find one?

Julia Watson: That’s part of why I’m putting this book out to the world. I have a really clear vision for what the middle ground could be, how we could start to explore these technologies and think about how they could change the way we design cities.

As cities keep on expanding and growing bigger, what’s the new way that cities will grow?

As cities keep on expanding and growing bigger, what’s the new way that cities will grow? We all have these utopian visions for cities but what if those utopian visions were really set within this type of thinking, drawing upon these types of nature-based technologies? What if cities really did sit within ecosystems, rather than the small applications of small ecosystems applied to facades in cities?

The book and this work is to put out examples and case studies, and seed contemporary designers who can take them and champion them. There are way better designers out there than me and I want them to take this, use it and apply it.

In the world of academia, we’re looking at the most cutting-edge, forward-thinking research transitioning to design. A lot of the time, academia and research is on the cusp of rethinking how the next wave of development will happen in practice. Given the number of issues that we’re having to confront today in our urban environment, in the world that we now live in, if we can just expand that horizon, there is so much potential.

Amy Frearson: What kind of response do you think you’ll get to the idea?

Julia Watson: It’s really funny that, across the board, there are three responses. The first is: ‘I can totally see this happening’. Then there’s some people who say: ‘Okay, but can it really apply to cities?’ Then there are people who just say no.

I love contemporary politics, so I’m really into understanding the way that frames our world and the way we see the world, and I think that it almost comes back to a political understanding about being visionary and forward-thinking. It’s like climate change at this point in time, it’s just a political argument, because the science can’t be refuted. Where there’s an adoption of the science, that’s going to reframe our world.

One project that I think is really interesting to talk about here is the UN-Habitat, the United Nations project looking at floating cities. People are really interested in this idea of floating cities. Yet in the book, there are two case studies of communities that have lived on islands. One of them is the Ma’dan that lived in the southern wetlands of Iraq for 6,500 years on floating islands. The other is the Uros that live on Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable lake in the world, on islands they construct from reeds, which last for 20 years. All around the world are people that live in aquatic environments.

We can’t really move forward using the same toolkit that got us to the place we are now. We can’t just keep reusing the high-tech and that type of thinking to solve the problems that created the problems. Looking at other communities might just give us the opportunity to say, what if we use high-tech and LO–TEK technology to think of this idea of floating cities? What do we think of these systems working with our natural environments? There’s so much opportunity with design and resilience, if we can leapfrog just being responsive. We’re really fascinated with sea-level rise right now because that’s what we see is the most imminent condition that we’re going to deal with. But following very closely on the coattails of sea-level rise is a huge die-off of trees in desert environments. It’s just the one thing that’s impacting the most people at a point in time.

There’s a new crisis coming to you, which is the wildfires in Australia and in California. People have been doing managed burn-off and using pyrotechnology as a technology. Communities all over the Americas and Australia have been doing that for millennia. They knew that they had to do that in those environments to create productivity but also to reduce threat. They’ve been using these things as resilient strategies for a very long time.

We need to shift this idea of superiority, to an understanding of symbiosis

I think we have to really expand our view of technology but really also be more predictive and be more prepared, not just in coastal ecosystems and coastal cities, but across the board. That’s why the book is divided into mountains, forests, deserts and wetlands. We’ve got to be looking at all these different environments and being resilient in all of them.

Amy Frearson: With climate change and the anthropocene already here, are you sure we haven’t run out of time to be resilient?

Julia Watson: No. I want to reframe the concept of the anthropocene, in a way. Because we came to industrialisation, we came to this period of time, we came to having a dissociation from nature through the Age of Enlightenment. It’s removed us from nature so that we either see nature as a threat or we see ourselves as the saviour of nature. I think that’s still like a fundamental thinking within this concept of the anthropocene and I want the book to dissolve that lens.

This is about symbiotic relationships, which are the fundamental building blocks of nature. These LO–TEK technologies are born of symbiotic relationships with our environment, humans living in symbiosis with natural systems. That’s what I think needs to change. We’re not superior, we’re not working against or threatened by nature, we need to be symbiotic with it. We need to shift this idea of superiority, to an understanding of symbiosis.

I think we need a new mythology, I keep on talking about this mythology of the contemporary world and the mythology of technology, but that mythology is really fundamentally underpinned by understanding that we’re not superior. It’s the only way that we’re going to move forward. I really do think there is a huge political will that’s just growing and growing. We’re seeing it like I’ve never seen anything like before. I think that it’s truly inspiring and unprecedented. To see a government completely disqualifying and disregarding that climate change is happening and then to have a groundswell of youth, of children, who are just politically up in arms, saying that you can ignore this anymore.

I can see change happening because I see it every day. There is a huge concern and architects are championing it, asking how they respond. This is a huge step in the right direction towards shifting, elevating and reframing how we build and how we urbanise.